Ursina (Year 12) writes about the historical and political importance of flamenco in this article. Taking us through the different periods in which flamenco evolved in, she explores how the contexts of the time affected Spanish society’s relationship with the dance and what it represents, whether that was due to associations with gypsies, the influence of the Catholic Church, the World Fairs of the early 20th century, the dictatorship of Franco, and the impact of tourism.

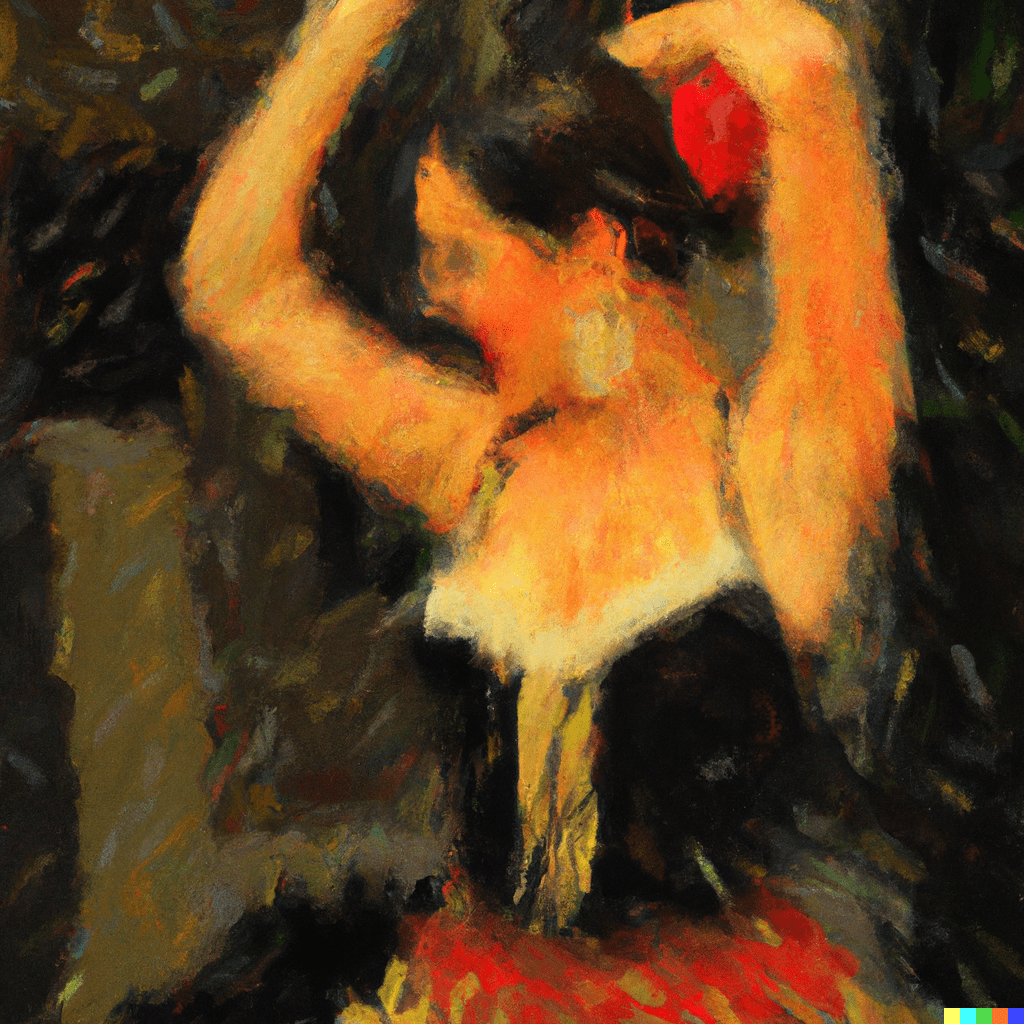

El flamenco es un baile muy popular e importante en España y es una parte de la cultura española, con un ritmo fuerte y los vestidos rojos. El mundo fuera de España suele estereotipar a la nación como habitada por bailaores flamencos y cantaores.

Sin embargo, dentro de España, hay una relación muy difícil entre el arte flamenco y la identidad nacional española. La reputación del flamenco se agravó a partir del siglo XIX porque el flamenco fue asociado con los gitanos. Las elites odiaron la conexión entre la cultura española y el arte flamenco porque el flamenco era considerado un espectáculo vulgar e inmodesto. Muchos años después de la Revolución Industrial, se le consideró como un entretenimiento que dificultaba el desarrollo hacia la modernidad.

Durante el periodo entre la Restauración y el comienzo de la Guerra Civil en 1936, había tres grupos que criticaron el flamenco; la Iglesia Católica, los políticos de izquierda y los líderes de los movimientos obreros revolucionarios.

La Iglesia Católica creía que el flamenco era un tipo de entretenimiento que conducía a la inmodestia y aumentaba la ruptura de la familia. Además, la Iglesia no pensaba que el flamenco siguiera las morales establecidas por la Biblia.

Para los políticos de izquierda y los líderes sindicalistas, el flamenco era una distracción para los pobres. Creían que el arte flamenco explotaba la pobreza de la gente y desviaba a los trabajadores de su deseo de convertirse en actores de pleno derecho en la búsqueda de una revolución, como la revolución rusa de 1917, que acabara con la desigualdad política y económica. En realidad, estos grupos utilizaron el flamenco como recipiente para contener su descontento con los males políticos, económicos y culturales de España.

Las numerosas Ferias Mundiales de principios del siglo XX impulsaron el flamenco y pusieron de moda a los gitanos españoles, sobre todo en París. El cante jondo recibió el beneplácito de los vanguardistas europeos como Claude Debussy, que había asistido a espectáculos flamencos en las Ferias Mundiales de París de 1889 y 1900, y lo encontró primigenio y auténtico. Eso llevó a intelectuales y artistas españoles como Manuel de Falla a elevar esta forma de flamenco a alta cultura. De este modo, el apoyo de los europeos fuera de España transformó el significado cultural del flamenco para los intelectuales y artistas españoles.

Sin embargo, después de la Guerra Civil, había menos representaciones de flamenco porque la Iglesia Católica lo repudió. Se promovió el baile folclórico y la dictadura quiso que España se limpiara de su tórrida reputación del flamenco.

Pero fue en 1950 que el régimen franquista empezó a necesitar el dinero. Por eso, promovieron el flamenco para impulsar la industria turística española. El régimen aumentó el número de locales que representaban el arte flamenco, animó a artistas flamencos profesionales a protagonizar en películas de Hollywood, y anunció bailaoras flamencas en folletos turísticos.

Después de la época Franquista en 1975, el papel del flamenco cambió otra vez. Los movimientos casi simultáneos por la autonomía regional dentro de España y el crecimiento de una cultura musical mundial complicaron la relación del flamenco con la identidad nacional española. La representación extranjera de España como tierra del flamenco ha sido explotada por espíritus emprendedores dentro de España. Esto no quiere decir que el flamenco florezca hoy solo para servir a los intereses del comercio.

Artistas, estudiosos y conservacionistas históricos han optado por promover su importancia histórica y artística tanto para España como para Andalucía. Por eso, se podría decir que el flamenco actual ha experimentado tanto una comercialización extrema como un renovado respeto artístico y académico, demostrando una vez más su compleja relación con la identidad nacional española y su importancia.

Flamenco

Flamenco is a very popular and important dance in Spain and is a part of Spanish culture, with a strong rhythm and red dresses. The world outside Spain tends to stereotype the nation as inhabited by flamenco dancers and singers.

However, within Spain, there is a very difficult relationship between Flemish art and Spanish national identity. The reputation of flamenco increased from the 19th century because flamenco was associated with the gypsies. The elites hated the connection between Spanish culture and Flemish art because flamenco was considered a vulgar and immodest spectacle. Many years after the Industrial Revolution, it was considered an entertainment that hindered the development towards modernity.

During the period between the Restoration and the beginning of the Civil War in 1936, there were three groups that criticised Flemish; the Catholic Church, left-wing politicians and leaders of the revolutionary workers’ movements.

The Catholic Church believed that flamenco was a type of entertainment that led to immodesty and increased the breakdown of the family. Moreover, the Church did not think that Flemish followed the morals established by the Bible.

For left-wing politicians and union leaders, flamenco was a distraction for the poor. They believed that Flemish art exploited the poverty of the people and diverted the workers from their desire to become full actors in the search for a revolution, such as the Russian revolution of 1917, that would end political and economic inequality. In reality, these groups used flamenco as a vessel to contain their discontent with the political, economic and cultural problems of Spain.

The numerous World Fairs of the early twentieth century promoted flamenco and made Spanish gypsies fashionable, especially in Paris. Cante Jondo was welcomed by European avant-garde artists such as Claude Debussy, who had attended flamenco shows at the World Fairs in Paris in 1889 and 1900, and found it original and authentic. This led Spanish intellectuals and artists like Manuel de Falla to elevate this form of flamenco to high culture. Thus, the support of Europeans outside Spain transformed the cultural meaning of flamenco for Spanish intellectuals and artists.

However, after the Civil War, there were fewer Flemish performances because the Catholic Church repudiated it. Folk dancing was promoted and the dictatorship wanted Spain to cleanse itself of its torrid reputation of flamenco.

But it was in 1950 that the Franco regime began to need the money. For this reason, they promoted flamenco to boost the Spanish tourism industry. The regime increased the number of venues representing Flemish art, encouraged professional Flemish artists to star in Hollywood films, and announced Flemish dancers in tourist brochures.

After the Franco era in 1975, the role of flamenco changed again. The almost simultaneous movements for regional autonomy within Spain and the growth of a world music culture complicated the relationship of flamenco with the Spanish national identity. The foreign representation of Spain as a land of flamenco has been exploited by entrepreneurial spirits within Spain. This does not mean that flamenco flourishes today only to serve the interests of commerce.

Artists, scholars and historical conservationists have chosen to promote its historical and artistic importance for both Spain and Andalusia. For this reason, it could be said that current flamenco has experienced both extreme commercialisation and a renewed artistic and academic respect, demonstrating once again its complex relationship with the Spanish national identity and its importance.